Welcome to issue 18, where I dive into two seemingly unrelated passions: my recent plunge into the masochistic world of gravel racing, and my 15-year love affair with camera lenses. This one is for all the camera aficionados out there, not necessarily the gear obsessed, but the ones who recognize these are the tools and experiences that define us.

Masochism in Lycra

Today, I am sore. My legs are speaking a language only gravel bikers understand — a dialect of deep aches and sharp complaints, mapping every rock, climb, and descent from yesterday’s battle. The irony, though, is I got peer pressured into doing this 200-km race, but couldn’t be bothered to wake up at 5:30 a.m. for it, so I ended up missing the start and joining the group at the 50-km mark.

All in all, I rode a respectable 150 km (90 miles) and I can’t even imagine how my race mates’ calves must feel. My quads are like smoldering coals, and my calves have turned into tightened, reluctant fists — my body’s honest accounting of what was borrowed against tomorrow’s comfort. Racing is a bit like drinking, except you skip the pleasant buzz and go straight to pain, suffering, and questionable life choices.

It’s interesting because I wasn’t planning to surpass myself. I was going to ride with my buddy Max, who was aiming for a reasonable 20-km/h average. Well, we ended up averaging 27 km/h throughout the race, which felt a bit frantic.

Every week I devote 6-7 hours to what I call “voluntary suffering,” whether it’s biking or running. Besides needing it for my mental health, I also adore the culture of sports. You share this common pursuit with people, a set of values, and in this day and age I want to belong to weirdly inspiring groups of people. Nothing bonds humanity more than collective masochism in moisture-wicking fabrics.

Racing, though? I don’t really do it. I race enough everyday in my career to keep the standards high, to win the best bids for projects, to put out work that is interesting to my audience. Sports are my hobby. Nobody expects a slide deck “by Monday” after I’ve gone on my bike ride. I’m a Sunday “athlete” in the same way the people who own Olympus cameras are photographers — enthusiastic, well equipped, and blissfully free from professional consequences. Frankly, it’s one of the healthiest relationships I have.

Am I making excuses for myself or should I just enjoy what works for me? I would love to hear your take.

My 15-Year Love Affair with Lenses

With NAB in the rearview mirror, I feel like this is the perfect time to talk about camera gear. I’ve spent the last weeks going through tens of terabytes of my photography archive to unearth anything resembling insight. I’m delighted to report that I found some. The questions I set out to answer are the following:

How does each focal length shape our visual storytelling and approach?

How do you pair the right lens with the right shoot?

How has my relationship with these lenses evolved over 15 years of professional work?

Every photographer has their trusted companions — pieces of glass that shape not just images, but entire careers. Over 15 years of shooting, I've captured more than 400,000 frames with these six distinctive focal lengths. Each one has become an extension of my vision, a unique voice in my visual vocabulary. From the expansiveness of ultrawides to the isolating precision of telephotos, these are the tools that have helped me translate the world as I see it. And today, I tell you what I think about them.

15-35mm

Out of all the lenses in this series, this is my most used by a country mile: over 143,000 photos shot with it! It’s the only lens that’s never left my camera bag, and it’s been with me on every fool’s errand. That’s not going to change anytime soon.

I absolutely adore ultrawides because they represent with the most accuracy how the natural world feels to me. Anytime I’m outdoors, it feels like I finally have room to breathe, to open up. This lens gives that same feeling to my photos. It leaves room for air, interpretation, and most of all, context — something I always strive for. Showing what’s beyond the edges of a scene is one of the most satisfying things I can do, and this is the only lens that empowers me to do that.

Its biggest party trick? How it exaggerates the relationship between foreground and background, making images feel layered and immersive. If the foreground has something worth showing, it draws you right in — and if it doesn’t, just zoom in to 28mm or 35mm and boom, you’ve got a solid portrait lens.

It’s common wisdom that there’s no perfect Swiss Army knife, but this one comes pretty close. Of course, you can’t overuse it — otherwise it loses its effect. Still, I feel like I’ve built my career on the back of this lens. So many photos, and honestly, so many I still enjoy looking at. After all, you’re only seeing 14 out of 140,000.

24mm

If you go by focal length, this is my second-most used. According to Lightroom, I’ve shot north of 71,000 frames at 24mm over the years. But focal length doesn’t tell the full story — there are 24-70mm zooms and 24mm primes. The one I’m talking about is the almighty 24mm f/1.4 prime.

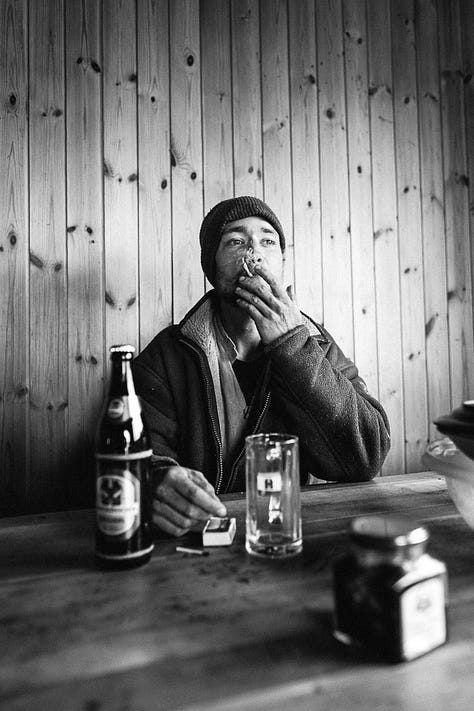

The reason I’ve used it so much is simple: the aperture. As someone who likes to shoot in low light, sometimes before sunrise and often after sunset, the ultra-low aperture makes a lot of sense. You get more light into your sensor without cranking the ISO too high. Cameras have come a long way, but I still find most things beyond 6400 ISO not very nice to look at, so any bit of light I can scrape “naturally,” I will.Besides the logical reason, there is love and affinity for the object. I love how heavy it is. I love how it sits on the camera. And, most of all, I love the way that it limits my field of view (versus an ultrawide) while still allowing me to make sense of the chaos within a scene.

Most of these were shot in Norway’s Lofoten Islands with a few exceptions. Cowboys: Colorado; surfers: O’ahu; farmer: Switzerland; alpine lake: Switzerland

50mm

How could I do this write up without mentioning the nifty fifty? People have praised this focal length because it supposedly mimics “the human eye” field of view. I’m not sure I buy that — my view of the world feels like I have a 15mm macro lens screwed onto my eye sockets. The field of view is gigantic but I can also get macro-close to things.

So, the 50mm… I’ve shot 8,161 photos with the old EF 50mm f/1.2, and 8,694 with the new RF 50mm f/1.2. That’s not counting the film shots. Overall, the 50mm is my fourth-most shot focal length, and it took me a while to love it.

It was too tight for the work I like to do, but I realized that if used wisely, it produces larger-than-life images. Akin to a medium format camera, especially if paired to the right camera body. It’s the perfect blend of neat bokeh and wide field of view.

70-200mm

Now let’s get into the less prestigious world of zoom lenses. Initially brought to market and perfected by Canon, these pieces of glass were meant to bring photographers closer to the subjects they couldn’t simply walk up to. The purists scoffed at these because they were improper: photographers had to get close to the action, often at the peril of their lives, and if you didn't do that, you were not a proper documentarian…

Nowadays, no one really cares whether you use one or not. In fact, 90% of the photographers I know have one of these in their kit.

If I had to give a name to my 70-200mm, it would be the “make it happen.” This glass doesn’t care about my excuses, it delivers solutions and makes a statement. Checking Lightroom reveals I've captured roughly 31,400 frames within this focal range. I typically reach for it when inspiration wanes or after exhausting possibilities with wider glass. But this seemingly practical relationship barely scratches the surface.

Many of my all-time favorite images were created with this lens. As someone drawn to cleaner, more "minimal" compositions, it's the ultimate isolation tool — sometimes to a fault, where it could be accused of producing overly simplistic images.

Yet this very quality is why I cherish the 70-200mm. It's a permanent fixture in my travel kit because the few times I left it behind, I inevitably found myself wishing I hadn't.

100-500mm

This beast isn’t just an extension of your vision; it's a tactical strike on distance itself. If the 70-200mm is the “make it happen” lens, this is the nuclear weapon — the Manhattan project in coated glass and weather sealing. It sees everything, but sees nothing at the same time. Point it at the wrong thing and it becomes useless. It really is a tool for separating subjects from their environment. My 17,000+ frames with it might seem modest until you consider its specialized applications.

This is what I pull out when I’m in front of a massive landscape, too big to capture with anything else. I draw a big breath (waiting for the stabilization to kick in) and methodically begin scanning at maximum reach. That’s when small compositions within the faraway landscape start to appear, almost like hazy miracles.

It won't win beauty contests with that protruding barrel, but this lens delivers extraordinary rewards for your patience.

You could argue that a lot of my best blue-hour work was done on this puppy, and you’d be right. Thank you for all these years, 100-500mm.

Watching

I enjoy re-watching this cycling film about the descent from Whitney Portal all the way to the desert floor — a mad 4,500-ft foot drop on smooth tarmac over a pretty short distance. I don’t know if I’d have the nerve to go this fast on a bike, a human torpedo wrapped in lycra, one pebble away from the worst imaginable road rash. Mad respect to those who ride it this fast.

This newsletter is edited by Danny Smith

Go Deeper

My editing presets : Speed up your editing workflow and achieve unique edits with my Lightroom editing packs. All photos in this issue were edited with them.

The Dolomites Photography Retreat 2025: Experience the still-authentic side of the Dolomites with a group of like-minded photographers led by Alex Strohl

Strohl x Moment 45L ultralight camera pack: “You no longer need to choose between a mountain pack and a camera bag. With this bag, you get both” — Moment

Adventure Photography Pro Workshop: Learn what it takes to make iconic work.

La 1er photo à été prise à chamonix : la montagne au vert

What's the sixth lens?